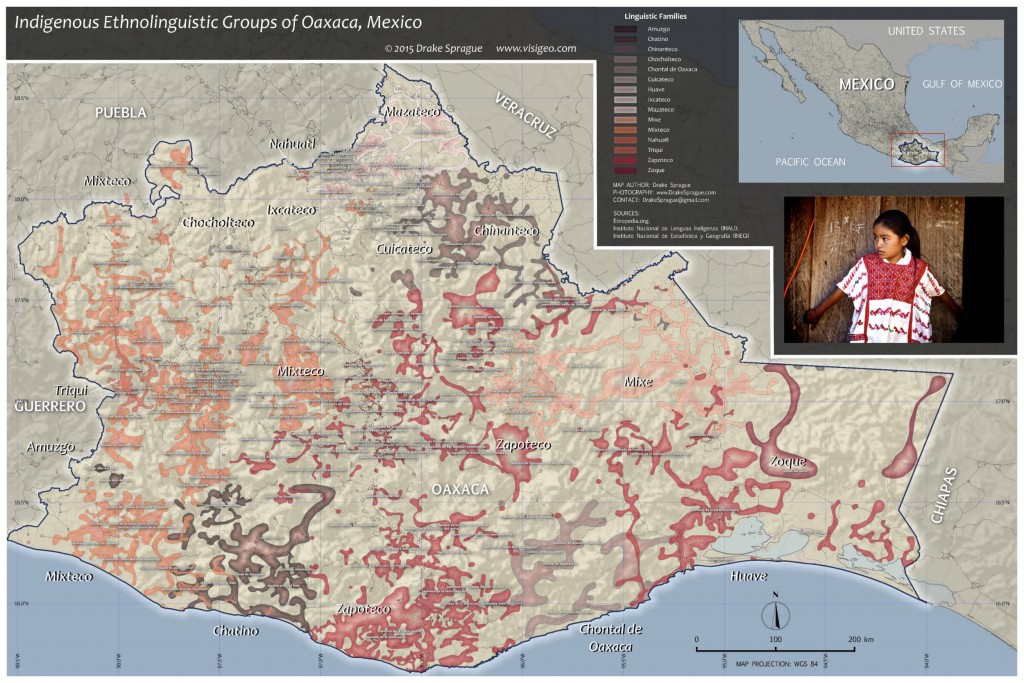

Mexico’s indigenous ethnolinguistic landscape is rich in diversity and complexity. While conducting research into the geography of ethnic people groups in southern Mexico from 2011-2013, we visited many indigenous communities. Amazingly, in Oaxaca state, by far Mexico’s most ethnically diverse, about 180 indigenous languages are still in use today. While many of these languages are disappearing, you will still encounter tribal communities where Spanish is hardly if at all spoken. Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (National Indigenous Languages Institute, or INALI) released its most recent Catalogue of Indigenous Mexican Languages in 2008, listing each known indigenous language and dialect with the names of the towns and villages where they are spoken. This data was compiled from multitudes of linguistic field studies, many conducted by Bible translators, and from government census notes. In spite of the geographic richness and detail of this data, surprisingly we could not find any existing maps prepared from it. Even after scouring the web, not a single map at this level of detail, even of Oaxaca, could be found illustrating the locations of Mexico’s hundreds of linguistic subgroups – which in most cases are very unique dialects unto themselves. The most detailed maps we could find depicted only the main language families.

As the lead geographic researcher for this project, Drake was determined to convert this wealth of information from a list of names and places into an actual map showing the spatial spread and divisions among each ethnolinguistic group. However, preparing the data for mapping would prove tedious, as the INALI catalogue was not published in a way that could easily be incorporated into a GIS workspace. For weeks, Drake used a GIS (both ArcGIS 10.1 and later a complete revision using QGIS 2.6) to build a shapefile with each language subgroup represented by its own polygon. We decided that since Oaxaca is the most linguistically complex state of Mexico, and because we were physically based there, it would be a logical starting point to begin the mapping process. Drake set up a GIS, populating the table of contents with a set of Mexico base map layers from Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía National Statistics and Geographic Institute, or INEGI. Administrative units and populated places would all be extensively used in context of each other throughout the project. With the GIS set up, Drake began building each polygon by hand, starting with the Zapotec languages subgroups, which at 62 subgroups (or dialects) is the largest indigenous language family in Oaxaca. Each subgroup would eventually be represented by a polygon feature encompassing all of the populated places where that language is spoken. Achieving this required careful analysis, with a tedious cross-check of each place listed in the catalogue against the GIS layers to accurately associate each language family and subgroup against its respective list of populated places.

Great care was taken to accurately visualize this data. Linguistic maps often use polygons to represent the locations of languages. However, they frequently do not allow those polygons to overlap in areas where they should. While topology, or seamless borders between unique features in a GIS, may ensure a smoother running system, mapping languages in this manner can be misleading. We wanted to show each overlap, so as to identify towns where multiple languages are spoken. Oftentimes, towns such as these are where large weekend markets occur, presenting opportunities to encounter people from different tribes. One of the biggest challenges though, and one reason why it would have been very difficult to write a Python script to organize and map the data from the catalogue, is the fact that in Mexico many places share the same name, or toponym. Many towns and villages also have multiple names and spellings. Both long and abbreviated names used to describe many towns. For example, “La Heroica Ciudad de Juchitán de Zaragoza” is also known as “Juchitán de Zaragoza”, and also simply as “Juchitán”. INALI uses the semi-condensed versions of such places in the catalogue, but there also happen to be multiple towns in Mexico named with some variation of “Juchitán”. Furthermore Drake came across at least a few misspellings and typos in the catalogue. For these reasons each populated place had to be scrutinized and considered in context of its respective administrative units, i.e., municipality and state boundaries. Firsthand area knowledge was also key to the analysis required for this project. Drake is very familiar with the geography of Mexico and the nuances of its place names relative to the mixed use of Spanish and indigenous toponyms. After several weeks, Drake completed a map of Oaxaca’s indigenous languages. He went on to create a map with more simplified polygons though using the same analytical procedures to map the rest of Mexico. The final challenge is how to graphically and distinctly represent each language family group and subgroup. Various color schemes have been tried, and it is still being developed.

Why is this level of linguistic data important? In one sense, it demonstrates how truly diverse Mexico is linguistically, hopefully encouraging efforts to understand and preserve these unique languages before they completely disappear. Another, practical application lies in the fact that southern Mexico is prone to disaster scenarios. The region experiences violent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, due to its proximity to three converging tectonic plates. It is also subject to the effects of El Niño, most notably the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) which directly affects levels of precipitation throughout the region, and has led to drought conditions. Infectious diseases are also of concern. The first confirmed death from the H1N1 Swine Flu epidemic in 2009 occurred in Oaxaca, Mexico. Advanced knowledge of a disaster prone region’s demographics, including language usage and ethnic identity (particularly in a tribal societies suspicious of outsiders) may be critical to a successful humanitarian operation. Mexico may be a predominantly Spanish-speaking country, but the same is not true among many Mexicans, necessitating maps such as this to geographically visualize as best as possible what languages are spoken and where. Of course, our main purpose for investing such time and energy into projects such as these in places like Mexico or the Amazon jungle is to help unreached people groups have access to the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Our prayer is that maps such as these will encourage and facilitate the work of missionaries by providing a strategic plan. Using the Etnopedia three-color indicator of Christian progress scale, seen here, you will see that most of Oaxaca’s indigenous people groups have only limited access to the Gospel. In South America, of the 400-500 Amazon and lowland tribes, about half have access to the gospel in some way. As we focus more on this region through ALTECO, we are finding much need for missionary work, especially by indigenous missionaries. We are training ministry workers such as these to conduct their own investigations and build their own maps that will guide them in the work. So much work is yet to be done! Please pray that the Lord of the harvest will raise up more laborers for the task (Matthew 9:38).